MDMA, PTSD & the Revision of our Pasts

MDMA, or ecstasy, is what you take before you go clubbing, right?

Or during your therapy session – which we may all need after Covid. And by the time it’s finally over, MDMA-assisted psychotherapy may actually be available.

MDMA isn’t a classic psychedelic like LSD. It doesn’t exactly alter your reality (though it might be able to change your past). The drug, which makes you feel happier, confident, and more empathetic, was synthesized in 1912, but wasn’t used until the 1970s, when it enjoyed a brief therapeutic career. In the 1980s it was sold on the street as a party drug, and was swiftly criminalized in 1985.

On the street, ecstasy is seldom pure MDMA; it’s usually cut with other drugs like amphetamine. It’s true that it’s not as harmless as classic psychedelics like LSD or psilocybin, and overdose or heavy, long-term use can have serious consequences. Its use at raves earned it a negative reputation in the press, but pure MDMA – when used sparingly – is relatively safe, and less addictive than most illicit drugs.

Anyways, now that psychedelics are becoming more acceptable, the media is changing its mind and shedding light on MDMA’s seemingly magical powers to alleviate – if not cure – PTSD. And these days, there’s more trauma than ever.

The more we talk about PTSD, the more it shows up. One could even say we live in a traumatized society. Around 10% of people in the US are estimated to have PTSD at some point in their lives, and about 3.5% of the population in any given year. But those are the official estimates.

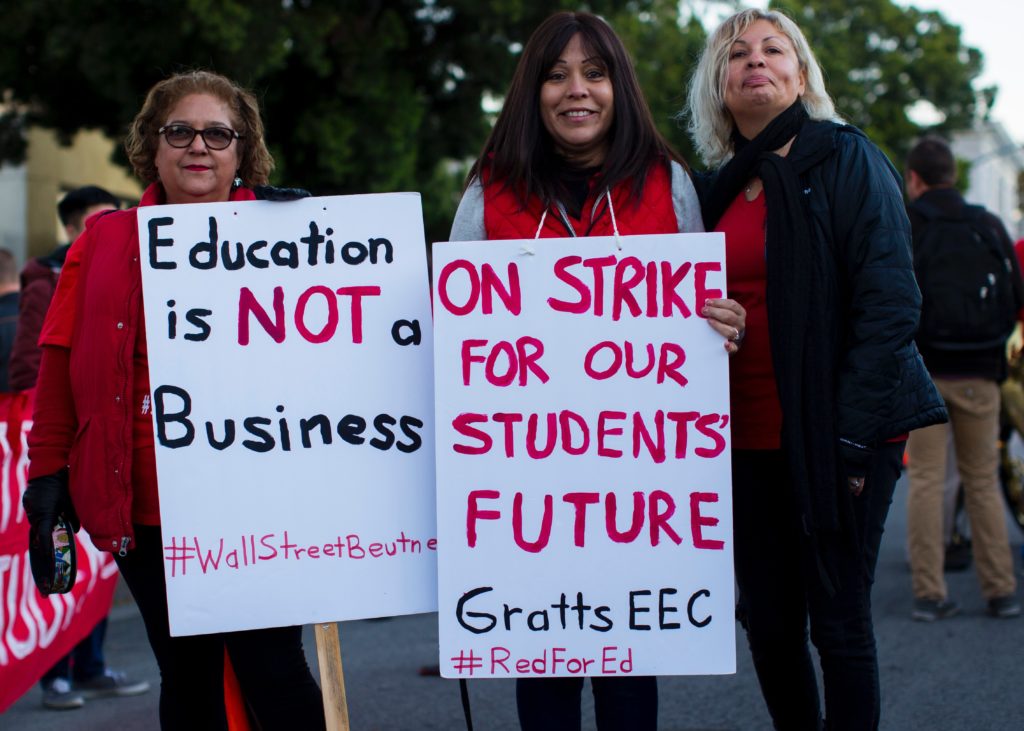

PTSD as a diagnosis was created to describe the symptoms of Vietnam War veterans. However we’re now learning that not only war, but everything from bullying, to living in poverty, to racism, to having Covid can cause PTSD. It’s also common in first responders like paramedics, who have to witness traumatic events on a daily basis. Whether or not we catch the “disease” depends less on the objective event as it does on the person, how they experience it, and the support they receive immediately afterwards.

Oppressed groups such as racial minorities and people in poverty are more likely to experience long-term stress and traumatic events. And those who don’t know they have PTSD are at greater risk of being retraumatized. This can lead to its new, stronger variant, C-PTSD (trauma is also mutating).

The only currently approved treatments for PTSD are SSRIs and psychotherapy, in particular exposure therapy. In exposure therapy, the patient recalls the traumatic event(s) in safe contexts over time. This is supposed to promote “fear extinction,” or an unlearning of the fear response. But it turns out that PTSD patients don’t like remembering their traumas over and over again, so exposure therapy has high dropout rates. Neither antidepressants nor exposure therapy are very effective in treating PTSD, with only around half of patients responding.

MAPS, an organization founded in 1986 to promote the research of psychedelics, has been at the forefront of MDMA research. MAPS decided early on to focus on MDMA because it’s the drug that best lends itself to therapy, and it had potential to treat PTSD, which has no strong treatment alternatives. They’ve been trying to conduct research with veterans since 1990, with no luck because of the stigma, despite the huge need; over one million veterans are on disability for PTSD.

“The real motivation, why I’ve kept going for so long, is that humanity as a whole is, I would say, massively mentally ill,” said MAPS founder Rick Doblin in an interview.

Towards an understanding of PTSD

More and more people with anxiety, depression, and addictions are realizing that these problems are rooted in trauma. This was the approach of early psychoanalysts, that psychological problems sprang from childhood trauma (though people like Freud created some weird theories around it).

Behavioral psychology and medical explanations have dominated since the mid-20th century, because it’s more profitable to treat human beings like lab rats than traumatized subjects. Acknowledging the sources of trauma would also mean addressing the deep inequities in our society. However the popularity of people like the doctor Gabor Maté, who says that all addiction is rooted in trauma, has helped bring trauma theory back.

And now that we now know a lot more about the brain, there’s some biological understanding of how PTSD works (and MDMA, too).

PTSD changes our brain structure. As we revisit the memory or it’s cued in our environment by a “trigger,” our bodies secrete stress hormones like adrenaline and cortisol to respond to the threat, and our bodies reactivate the fight, flight, freeze, or fawn response. Our hippocampus measures and regulates cortisol, but too much wears it down, and so it shrinks. Meanwhile, cortisol continues to signal the the amygdala, which processes emotions like fear, and grows as we maintain a state of hypervigilance. The ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), which regulates the amygdala, emotional responses, and our self-control, also shrinks and becomes hypoactive, leading to difficulties with emotional regulation. A deactivated vmPFC and smaller hippocampus in PTSD translates to deficits in thinking, learning, and memory, while a larger amygdala makes people more sensitive to fear.

Of course this hypervigilant state was meant to respond to real threats in our environment, but PTSD is usually maladaptive, playing traumatic memories or their reminders and fear responses on loop.

It’s worth noting that memories aren’t only visual. As a study of traumatic experience notes:

“Episodic memory can present itself in parts… [it] might appear as an inner vision, a sound, or just a hint – a brief sensation in the belly or a strong pain in the chest.”

MDMA-assisted therapy offers hope

“We know from brain scans of PTSD patients that PTSD changes people’s brains, and MDMA can change it back in almost the exact same way,” said Doblin.

“So, where PTSD increases activity in the amygdala, MDMA decreases activity in the amygdala. PTSD decreases activity in the prefrontal cortex, MDMA increases activity in the prefrontal cortex. PTSD makes people feel isolated, alone, and mistrustful, but MDMA builds trust and connection.”

MDMA increases the availability of the neurotransmitters serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine, while releasing hormones including oxytocin, cortisol, prolactin, and vasopressin.

This neurobiological cocktail puts subjects in an ideal therapeutic state. It provokes a sense of peace and safety, makes them more introspective and open, and more trusting in their relationship with their therapists.

And in combination with psychotherapy, it appears that MDMA heals trauma in about two-thirds of cases.

It wasn’t with veterans, but MAPS was finally able to conduct their first study in 2008. Their trials were such a success that the FDA granted MDMA-assisted psychotherapy Breakthrough Therapy Designation in 2017, fast-tracking the research.

In 2020, MAPS aggregated the follow-up data for six phase 2 trials of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy. All of the trials were conducted similarly, with participants undergoing eight psychotherapy sessions, two of which lasted eight hours and involved MDMA.

At treatment exit, 56% of participants no longer met the criteria for PTSD. However in the one year follow-up this number had increased, and 67% of participants no longer met the criteria, while over 90% had a clinically significant reduction in symptoms. These are magical numbers. A follow up of an older study is even more promising, suggesting that the benefits of MDMA treatment for PTSD canlast at least 3.5 years.

MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD is now in phase 3 trials, which are expected to be completed in 2022, and the therapy could be approved by the FDA as soon as 2023.

In case the government wasn’t sold on the benefits, MAPS produced a separate study estimating that making MDMA-assisted psychotherapy available to just 1,000 patients with PTSD would reduce general and mental health care costs by $103.2 million over 30 years. For a million veterans, it would save $103.2 billion.

Positively changing our memories

MDMA-assisted psychotherapy is thought to treat PTSD through memory reconsolidation. It increases the connectivity between the hippocampus and amygdala, which may indicate a heightened capacity to emotionally process fear-related memories.

It turns out that when we recall memories, they become malleable. There’s a small window in which they “reconsolidate” and we can modify and update them. The events themselves may not change, but the way we remember them, and especially the feelings we have associated with them, do.

We do this all the time. For example if you once looked back on a fun experience with a partner fondly, but then found out that partner cheated on you, you might remember that same experience differently – perhaps with sadness, anger, or a sense of betrayal.

When we recall trauma memories and our adrenal receptors in the amygdala are activated, those memories are reinforced from a place of fear. Continually recalling the same memories with the same emotions may be what underlies the long-term nature of PTSD.

MDMA therapy is like the opposite of that. The key is reconsolidating memories in a positive state. First you enter a safe, happy state of mind, and only then do you recall memories with your therapist, process them, and reconsolidate them.

MDMA allows us to visit the ghosts from our pasts from a place of empathy or compassion. Without fear, we can see through them and give them new meanings. We can make peace with them, and lay them to rest.

Can you use MDMA to treat yourself? You can try, but I wouldn’t recommend it. You’ll need the psychotherapy not only to help you process your trauma and integrate your experience, but to pick up the pieces of your life that trauma has left in its wake.

Doblin says the end goal of the MAPS project is “mass mental health.” If phase 3 trials are successful and MDMA-assisted psychotherapy is approved by the FDA, MAPS plans to focus on researching group therapy for PTSD, as well as other indications for MDMA.

Because MDMA is thought to stimulate prosocial behavior, MAPS is also studying MDMA-assisted psychotherapy as a treatment for social anxiety in autistic adults. It’s also being investigated for couples therapy and addiction.

Community gardens make cities more beautiful and grean, and provide fresh and healthy food for the communities they’re in. If you already know how to garden, you can start to grow your own food, while meeting and teaching others. And if you don’t know how to garden, you can learn! The other gardeners will give you free tips, and many community gardens even offer classes. Learning, socializing, and eating healthy foods are all ways to nourish your brain and help heal trauma.

Community gardens make cities more beautiful and grean, and provide fresh and healthy food for the communities they’re in. If you already know how to garden, you can start to grow your own food, while meeting and teaching others. And if you don’t know how to garden, you can learn! The other gardeners will give you free tips, and many community gardens even offer classes. Learning, socializing, and eating healthy foods are all ways to nourish your brain and help heal trauma.