The neuroscience behind ayahuasca’s efficacy

By Katalina Lourdes

Ayahuasca is an Amazonian tea traditionally used by shamans for making contact with the spirit world, as well as for sorcery, divination, religious ceremonies, and healing. The decoction, which typically combines the vine Banisteriopsis Caapi with another plant containing dimethyltryptamine (DMT) like Psychotria Vidris, has been growing in popularity in Europe and North America over the past two decades for its powerful therapeutic effects.

Research studies have been rolling in to confirm innumerable anecdotal reports of ayahuasca’s ability to heal disorders like depression, addiction, and PTSD. With the psychedelic renaissance underway, entheogens are the hottest new area of research in mental health. Not just ayahuasca, but magic mushrooms and LSD are being researched at universities and consumed medicinally in legal and underground settings around the world. However the benefits of ayahuasca are rumored to be above and beyond those of its counterparts. At least one study has found that ayahuasca experiences are more positive and their effects more enduring than experiences with LSD, psilocybin, or plain old DMT. Ayahuasca users also tend to have higher levels of well-being than LSD or psilocybin users.

If you’ve seen a documentary featuring Dr. Gabor Maté, like The Wisdom of Trauma, you may know that ayahuasca has also received attention for its potential to heal cancer and other chronic diseases.

So what makes ayahuasca so powerful? Does the answer lie in biology? Or could environmental factors explain ayahuasca’s extra magic? Could this panacea’s efficacy come from the supernatural realm?

Is it even possible to know?

Does it matter?

Maybe not. However by looking at the various factors influencing the ayahuasca experience (biological, physical, social, cultural, and spiritual) we can at least hope to gain some new insights and ideas about why we trip, and how to trip well.

I’ll begin by summarizing the science of the so-called civilized, with a deepish dive into the neurobiology of ayahuasca.

The neuroscience of ayahuasca

Disconnecting & transcending

Humans have been resetting our brains with psychedelics for thousands of years. And they work. Like a switch that lights up your unconscious – maybe you see your shadow, your guardian angel, your spirit animal or your inner child. Turn it off and on again, and the next day when you wake up you may find that your depression has lifted. You may even have a death and rebirth experience. You may find that the experience changes you profoundly as a person. It’s okay to say goodbye to people we were or parts of ourselves – that’s how we grow. Hanging on to the ego is where trips can sometimes go south. We have to let go and trust in the plant spirits. Or the science, if you prefer.

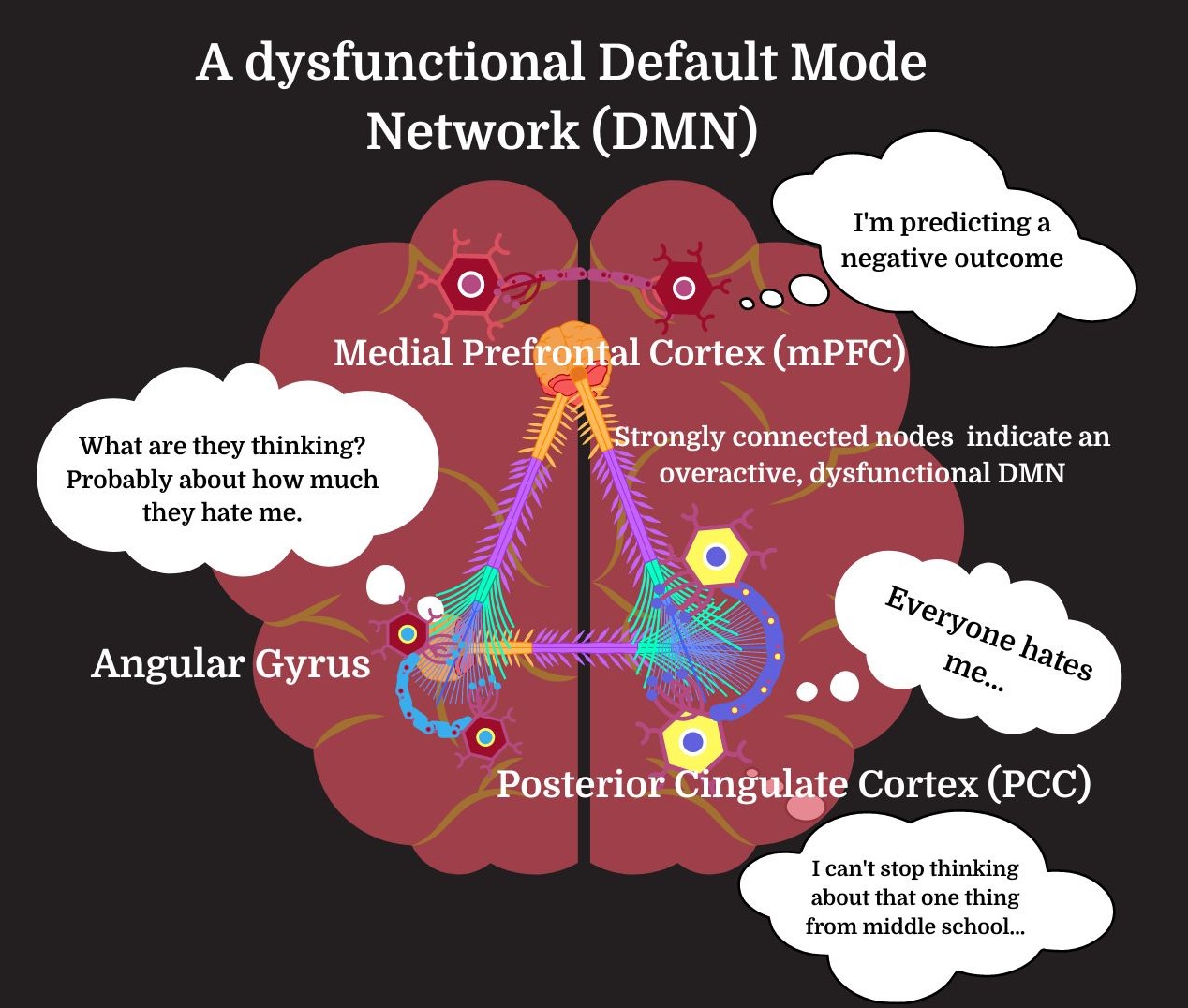

Like other tryptamines, DMT disrupts major neural networks, those well-worn pathways connecting different brain regions. One such network is called the default mode network (DMN), and its disconnection is liberating. Known as the seat of the ego (and of depression), at higher doses DMT and other psychedelics thoroughly deactivate the DMN, decoupling its various nodes, inducing ego death and unleashing intensely meaningful and mystical experiences.

The DMN’s main nodes in the brain are the medial prefrontal cortex (the mPFC), the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), and the angular gyrus. Together, these nodes are responsible for many of our mental processes – especially dysfunctional ones.

The DMN directs our attention internally – but not in the same way we turn inwards with ayahuasca. The DMN is active when we’re daydreaming, recalling our pasts, planning for the future, and entertaining complex social thoughts like ethical judgments or mentalization about another’s state of mind. The construction and maintenance of a stable sense of self also takes place in the DMN. So it’s not unimportant – but the DMN has a real dark side.

At the center of the DMN is the PCC. The PCC is implicated in just about every disorder of the mind you could think of from Alzheimer’s to depression, anxiety, ADHD, autism, and traumatic brain injury.

The PCC is highly sensitive to our emotions, which triggers it to call forth relevant autobiographical memories. This could be a way of monitoring our experiences and comparing them to our pasts, thereby ensuring the continuity of the ego by reinforcing our self-concept and bringing the same person, thoughts, or behaviors into the present.

However a hyperactive PCC will take that self-referential thought and go wild. It will obsess – turning attention not just inwards but against oneself with negative self-criticism, self-aggression, and doubts, leading to a spiral of rumination that makes it difficult to pay attention to what’s going on outside ourselves. Creating our own personal hell.

It seems to me that the PCC is like a muscle; the more you use it, the more it grows – but its growth is malignant.

Meditation, on the other hand, deactivates the PCC. And if your PCC begins to shrink, well praise be – you may become a boddhisatva after all. You’re on your way to Nirvana.

A recent study found that members of the Santo Daime, the Brazilian ayahuasca church (where ‘daimistas’ may take ‘daime’ as frequently as once a week during religious rituals), have significantly thinner PCCs than the rest of us. The thinness of the daimistas’ PCCs was directly correlated with the duration of their use and the quantities of daime they consumed. And the thinner their PCCs, the higher the daimistas scored on a scale measuring “self-transcendence.”

Freeing our depths from logical repression

The neocortex is the outer layer of the brain, where our gray matter and logical thoughts live. Under normal circumstances, the neocortex controls the rest of the brain through neural networks like the DMN. Serotonergic psychedelics like DMT deactivate and decouple these networks, disabling the top-down control that the neocortex usually exerts over the more ancient, emotional limbic midbrain. This allows repressed feelings and memories to surface from deeper brain areas without being suppressed by the thinking, judging neocortex.

DMT also deactivates our right amygdala and binds to the serotonin 5-HT1A receptor , which is thought to decrease anxiety. These are like safety mechanisms that help protect us from being frightened by any traumatic content arising from our unconscious, or from being overwhelmed by whatever other vision ayahuasca may present us with. These mechanisms may also help us feel safe enough to confront and process any sensitive material that comes up for us in new and creative ways.

The inhibition of top-down cortical control also allows a more anarchic, “entropic,” pattern to form in the brain. Not only do psychedelics disconnect normal neueal pathways, but new ones begin to emerge, as nodes that don’t usually talk start to communicate. This opens us to new ways of thinking, ideas, and insights.

Like other psychedelics, DMT binds to the serotonin-glutamate combination receptor 5-HT2A/mGlu2. How does this play out in the brain? Serotonin doesn’t have its own special type of neuron, but is expressed on many different neurons. The 5-HT2A/mGlu2 combo receptors are expressed on both excitatory pyramidal cells (which release the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate) and inhibitory interneurons (which release the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA) in the neocortex. However the mGlu2 receptor is an inhibitory glutamate receptor, and it prevents the release of glutamate into the next neuron. So the activation of this receptor creates an inhibitory pattern in the brain. This is what quiets the neocortex, and opens the brain up to information buried deep within.

DMT’s activation of the 5-HT2A/mGlu2 receptor also causes the release of what’s called a G protein at the receptor. The protein is released into the neuron, spurring a series of intracellular processes that end up stimulating the production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein that’s essential for the development and sustained health of neurons.

In pathologies such as depression, stress, and PTSD, neurons fry and their dendrites wither. Through a dramatic uptick in BDNF in the brain, neurons begin to flourish – growing new dendrites, forming new connections at synapses, and nourishing baby neurons from the dentate gyrus. This neuroplasticity means there are more neurons, and they’re healthier and more able to communicate with each other, and new connections form in the brain, creating new neural networks and thought patterns. These new neural networks provide an escape from the well-worn, dysfunctional thought loops of the DMN that we may have been trapped in. If we nurture these new thoughts, they can turn into permanent changes in our attitudes, behavior, and lifestyles. We can shed our old skins and become new people.

O Sigma-1

All serotonergic psychedelics are understood to work in the ways described above, not just ayahuasca or DMT. However DMT binds not only to the 5-HT2A/mGlu2 receptors, but a receptor called Sigma-1. The Sigma-1 receptor “has so far been implicated in illnesses like Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, cancer, cardiomyopathy, retinal dysfunction, perinatal and traumatic brain injury, frontal motor neuron degeneration, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, HIV-related dementia, major depression, and psychostimulant addiction.”

Activation of the Sigma-1 receptor through DMT may be a way to prevent, heal, and even cure some of the diseases listed above. How? Well, Sigma-1 protects against oxidative stress, low grade inflammation (LGI), and endoplasmic reticulum stress. All of these cellular stresses are closely related to and exacerbate one another. Oxidative stress can lead to cancer and apoptosis (cell death). Research increasingly implicates LGI in most chronic diseases, including disorders of the brain. The endoplasmic reticulum is responsible for protein folding, which goes awry in diseases like Alzheimer’s. Sigma-1 also supports mitochondrial activity and cellular survival, thus promoting neuroplasticity and preventing the neural degeneration typical of many brain disorders.

B. Caapi to the rescue

Banisteriopsis Caapi, the vine that constitutes half of a typical ayahuasca recipe, contains no DMT, but shamans have long considered it to be the key ingredient in ayahuasca. It contains alkaloids that prevent the immediate breakdown of DMT in the gut, allowing us to enjoy the trip for a few hours instead of seconds. These alkaloids have also been found to stimulate neurogenesis – the growth of new neurons in adults.

What could be better for your brain? I mean, maybe bolstering the brain’s immune system to kill free radicals and prevent cell death, which B. Caapi also does. It turns out the vine also has compounds with anti-inflammatory effects in microglia, protecting and strengthening the brain’s immune system. So ayahuasca doesn’t just heal by way of DMT, and scientists are now studying B. Caapi to find ways to prevent neurological diseases.

This short neuroscientific overview may explain some of ayahuasca’s proclaimed magic, its curative powers – but there are more variables at play in the complex interactions that occur between the biological, personal, physical, and social worlds.

In Part II, I’ll introduce the epistemologies of Peruvian shamans (though I’ll hardly be able to do them justice), before returning to Western thought and looking at aspects of set and setting in ayahuasca ceremonies. Hopefully, Spirit will guide me away from too much reductionism or empiricism in the realm of the personal, social, and spiritual, where most things are invisible and immeasurable.