30 individual and collective ways to heal trauma

By Tina Phillips, MSW

Overcoming trauma is a process. Trauma, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can be caused by an event or an emotional experience in which a person felt a threat to their life and safety.

PTSD and in the event of chronic or repeated traumas, C-PTSD, can present itself as emotional distress, distrust of others, fear and anxiety, and emotional dysregulation. It can also cause depression, flashbacks, and avoidance.

There are both individual and collective ways to heal trauma. Some individual ways to heal from trauma are self-care, therapy, art, journaling, and using workbooks.

Collective ways to heal trauma may include group support, volunteer work, social support, and even activism. Activism and community advocacy can help us have hope for the future, and empower us to take action now that can improve our own lives and help our communities.

Both individual and collective methods are worthwhile endeavors. No solution is one size fits all, and it can take experimenting with different techniques and coping skills, and combining them to fit each individual.

“Developing an inner refuge where we feel loved and safe enables us to reduce the intensity of traumatic fear when it arises.”

Tara Brach

Individual methods

Individual methods of overcoming trauma can help us to feel our feelings and understand our experiences instead of numbing and avoiding them. These tools can help us embrace and process emotional pain and how it shows up for us in our bodies. Feelings can include shame, negative thinking, flooding and repeated thoughts, and low self-esteem.

In addition, these methods can foster self-compassion and build a relationship with ourselves, allowing us to get to know ourselves better by opening up buried wounds of the past. Some individual ways to help heal trauma are to get moving and exercise. Don’t isolate, use stress reducing techniques, take care of basic health needs such as getting proper nutrition and sleep, and seek professional help if necessary.

Dawn Serra

Some stress reducing techniques that heal trauma

Deep breathing and progressive muscle relaxation

Deep breathing helps more oxygen get to your brain and triggers the parasympathetic nervous system, promoting relaxation. It also connects one to their own body and brings awareness to the rhythmic sound of your breath, bringing centered calmness. In addition, when we tighten a muscle and then release it, it causes deeper relaxation in that muscle. This can promote relaxation in the entire body if done one muscle group at a time. The body is connected to the mind, and thus this causes relaxation in the brain as well.

Using soothing scents, sights, sounds, or touch

Scent can help us relax, via our limbic system, which connects to emotion and memory. Relaxing smells can lower stress levels, promote soothing feelings, and help invoke positive memories.

Pleasing visuals can have a calming effect, helping us to destress and bringing us comfort. This can be as simple as looking at pictures of landscapes, ocean, animals, nature, or going outside and looking at nature.

Listening to music, the ringing of bells, the sound of ocean waves or rain, binaural beats, and guided meditation can all help reduce anxiety, decrease stress, tap into good memories, focus the mind, and promote enjoyment and positive feelings.

Touch can soothe us, make us feel connected, and increase well-being. Touch has been proven to lower heart rate and blood pressure, lower stress, and increase oxytocin. From a hug to a massage, touch comes in so many forms. Even a weighted blanket can help ease our anxiety and help us fall asleep. There are so many ways to bring touch into our lives and collect its benefits.

Grounding activities

People with PTSD can dissociate, or have the sense of not being themselves or in their body. In this case, grounding helps bring us back into our body and the present and feel our feelings. It can be as simple as lying on the floor, or anything that slows us down or engages us physically such as meditation, dancing, or going for a walk. When people are experiencing panic attacks or flashbacks, grounding is also used as a tool of distraction, drawing awareness away from anxiety by focusing on a cue which engages the five senses.

Mindfulness practice

Mindfulness practice is about bringing awareness into the present moment. It’s a way we can observe ourselves without judgement and getting overwhelmed. When practicing mindfulness people bring awareness into their bodies, feelings, and thoughts and try to bring them into balance.

Mindfulness is about paying attention. Not to the past or the future, but right here and right now. Mindfulness can promote stress reduction, help anxiety and depression, and quiet the mind so it becomes more focused and calm.

Meditation

Meditation promotes deep relaxation, focuses attention, reduces stress, increases awareness, reduces negative thoughts, can boost imagination and creativity, and increases tolerance and patience. There are so many different kinds of mediation and various methods – despite popular belief that it looks one way, and that way is hard. Learn more about it and you may find one that is right for you.

Workbooks

Workbooks are a great way to get the tools that therapy teaches you without the price tag. They range in price, but for around $15, you can get a workbook that will teach you about depression or anxiety and techniques on how to reduce them.

Art

Art, for example painting, beading, knitting/crocheting, adult coloring books, drawing, collaging, photography, origami, mosaics, etc., can all be healing.

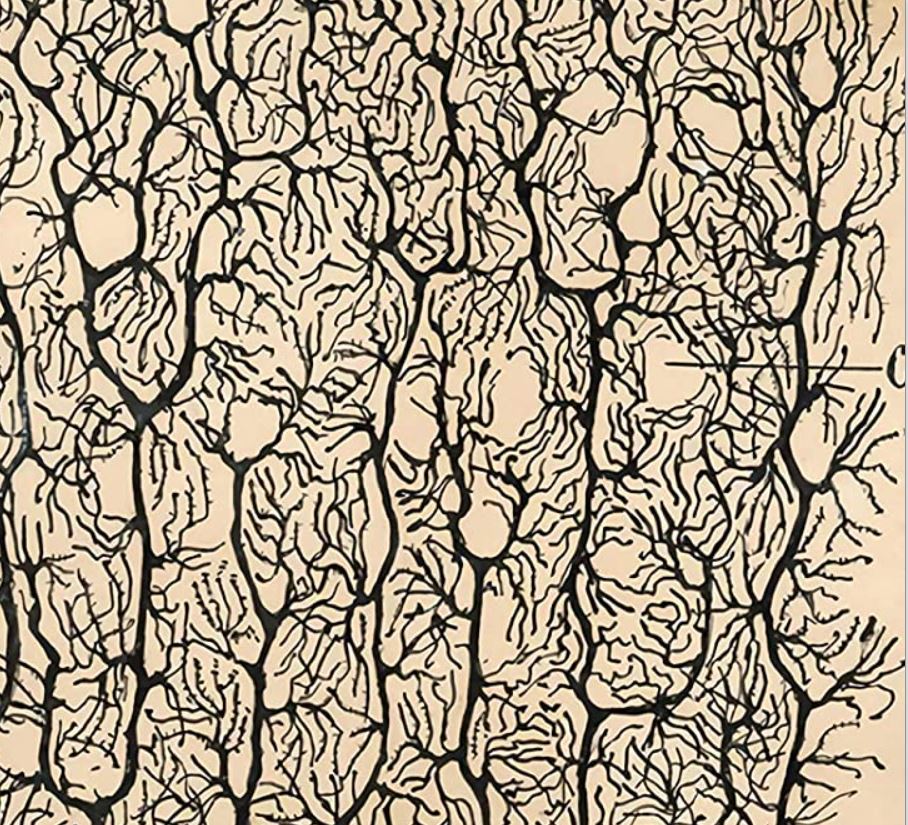

Art helps us make more connections in the brain and connects our minds to our bodies. It helps us tap into our creativity and get in touch with our feelings, and it can help promote enjoyment, rhythm, and soothing feelings.

Journaling

Journaling is a cost effective way to put your traumatic experiences down on paper. Writing is a creative expression that can help our brains process information, reduce stress, and even boost our immune system. Writing can help us tap into the meaning of our experiences and see our own growth from them, as we re-read and reflect on our story. It’s also a great way to vent, without anyone else having to listen to it or react. It’s a way for you to get it all out with privacy.

Get in nature

Nature can reduce negative feelings such as anger. Nature reduces stress, and promotes positive feelings such as joy. Nature tends to help both body and mind, and has been proven to reduce blood pressure, relax muscles, lower heart rate, and lower stress hormones. Nature can be soothing, help us feel connection, bring us balance and calm, and help us feel more resilient and focused. Nature can even distract us from our pain.

Video games

It may surprise some, but studies show video games can be an effective way to treat trauma. Video games have a mindfulness-like effect, as well as a soothing effect through repetitive tapping and button pushing. They can also provide social connection, be used as a tool of distraction from painful symptoms, and help create meaning. Video games can be affordable and played in the privacy of one’s own home.

Get a pet

It’s been proven that stroking the soft fur of a pet can increase our levels of oxytocin. In addition, having a pet can decrease stress levels, lower blood pressure, lower risk of a heart attack, and help ease depression, anxiety, and stress. A lot of these benefits come from playing with, walking, feeding, and petting a pet. Pets can help us get out of bed because they need us. (The secret is, we need them, too.)

ASMR (Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response)

ASMR can help people relieve bad moods, create soothing feelings, reduces chronic pain, and helps reduce stress, depression, and anxiety. ASMR can also help people to relax, fall asleep, and uplift their mood.

Join in person support groups, peer support groups, Facebook support groups, or other online support groups

The great thing about support groups is that you’re surrounded by other people who are going through the same thing you are. It instantly decreases your feeling of being alone or isolated. You are validated by others who confirm your experience and reflect back your own experience. This brings comfort and builds social bonds. Many groups are also easily accessible and affordable or free. Peer support is really a great way to help others as well, and feel like you’re giving back in return for advice and support you received from others.

Go to therapy

Therapy helps people process the trauma they have been through. Therapy also teaches a person about trauma and how it could be showing up for a person. Therapy helps a person talk about their traumatic experiences, and helps guide them to express their feelings in healing ways. Therapy can help you develop a narrative which is compassionate and accurate based on how trauma shows up for you and how it affects the brain.

Therapists provide psychoeducation, teach therapeutic techniques and tools, and use therapeutic techniques to treat trauma and reduce symptoms such as depression, anxiety, hyper-vigilance, or flashbacks. Therapy can help people regain a sense of power, increase self-esteem, help with daily functioning, teach people healthy coping and self-soothing skills, and help them develop resilience. Therapy can also help reduce stress, negative feelings, and self-harm. There are many types of therapy, and some may work better than others for you depending on your situation and needs.

Herbs, supplements, & alternative medicine

Collective methods to heal from trauma

Collective methods of healing trauma are also a creative way to channel our feelings and look outside ourselves for connection. Activism can help people share their feelings, empower themselves, receive validation, and create purpose and meaning for those who may feel they have lost their way.

These collective methods focus on helping others and giving back, building community ties, and fostering healthy relationships. These tools can help one process grief and loss, decrease loneliness and isolation, create safety trust, and build resilience. Furthermore these methods can help create positive change, can be transformative for the individual and society, and help a survivor take their power back.

“The most beautiful people we have known are those who have known defeat, known suffering, known struggle, known loss, and have found their way out of the depths. These persons have an appreciation, a sensitivity, and an understanding of life that fills them with compassion, gentleness, and a deep loving concern. Beautiful people do not just happen.”

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross

Some systemic solutions that help heal trauma

Building social support networks

Traumatic experiences can isolate us, or cause us to self-isolate. However human relationships are extremely important for mental health and having a sense of belonging and support. Trauma survivors can help heal by finding social support through support groups, spending time with their friends and family, becoming part of spiritual communities, and building positive relationships with coworkers.

Volunteering

Volunteering is a great way to make social connections, to build community, to help yourself feel positive feelings, and create purpose and meaning. Volunteering can also be fun, be good for building work experience, and helps increase leadership skills.

Writing for an audience

Writing for an audience can help one express deeply held experiences in order to help others feel less alone and isolated. It can also help others to find techniques and ways to improve their own lives. This can be very fulfilling and also healing for the writer, whose lived experience can both be written about and expressed, and also read by many people, helping bring meaning and purpose, resilience, and courage to both the writer and the audience.

Advocacy

Advocacy work helps us raise awareness of our own cause. It helps us when we speak up for others who feel voiceless, helps us build resilience and courage and promote these in others, helps us use lived experience to fight for better policies and treatment for others, helps break down stigma, and be effective in promoting better wellbeing for people like us. Advocacy helps us feel less powerless, as we see the benefits of our work demonstrated in tangible outcomes and improved lives.

Join a community garden

Community gardens make cities more beautiful and grean, and provide fresh and healthy food for the communities they’re in. If you already know how to garden, you can start to grow your own food, while meeting and teaching others. And if you don’t know how to garden, you can learn! The other gardeners will give you free tips, and many community gardens even offer classes. Learning, socializing, and eating healthy foods are all ways to nourish your brain and help heal trauma.

Community gardens make cities more beautiful and grean, and provide fresh and healthy food for the communities they’re in. If you already know how to garden, you can start to grow your own food, while meeting and teaching others. And if you don’t know how to garden, you can learn! The other gardeners will give you free tips, and many community gardens even offer classes. Learning, socializing, and eating healthy foods are all ways to nourish your brain and help heal trauma.

Restorative and Transformative Justice programs or circles

Transformative Justice is a framework communities can use to address violence and abuse outside of the criminal justice system. It’s an approach that seeks to create accountability, safety, and healing within communities harmed by trauma, without perpetuating violent reactions or behaviors.

Movementand community building

Some people’s experiences of mental health treatment has itself been traumatic. This can be because of the stigmatization that comes with some mental health diagnoses, misdiagnosis, or experiences of forced institutionalization or dehumanization in psychiatric care. There are networks and communities of mental health survivors that critique the mental health system and advocate for it to be more patient-led. Joining one can give survivors a voice and be a source of social support, especially for those who have been traumatized by psychiatric institutions.

Join a union

Economic disempowerment is a major contributor to mental health problems. Unions are a way to address disempowerment at the workplace and declining wages. Unions can build a community of solidarity at your work, uniting workers to fight for higher wages and better working conditions. A union will also support you if you’re being harassed on the job, and educate you as to your rights at the workplace.

Join or start a coop

Coops are a way to bring power back into our own hands and the hands of our communities. There are several different kinds of coops (and collectives). Worker coops are businesses that are owned and operated by the people who work there, so they tend to have better working conditions and serve the needs of their communities more than traditional hierarchical businesses. Consumer coops, like many local grocery stores, are owned by the people who shop there, and often have gathering spaces or offer events and services to the community. Having strong communities and socializing is good for our mental health, and can help us build support networks and overcome isolation and trauma.

We are working through trauma and towards healing both as individuals and as a collective. It takes many shapes and forms. It’s up to us to design the toolkit that works best for us throughout our journey. Hopefully this has inspired you as a jumping off point to do some healing work of your own.