A visit to Hekate’s domestic chapel

By Katalina Lourdes

I rode up towards Mas Castellar on the local train to Cerbère, a town just across the border on France’s Mediterranean coast. Cerbère is French for Cerberus, the Hound of Hades – a three-headed dog that guarded the underworld. I’m amused, because I’m headed to a Hellenistic temple that was also a site of ritual dog sacrifice.

In the ancient Greek world dogs were associated with purification, and sometimes used to cure diseases. A few miles away, dogs would have roamed the underground chambers of the temple of Asclepius in Empúries, licking sick pilgrims who came to be healed by the god through their dreams.

Dogs were also symbols of protection, and sacred to the goddess Hekate. Known as Prytania (“invincible Queen of the dead”), Phosphorus (“the light bringer”), and Soteira (“Savior”) among other epithets, Hekate is a goddess of protection, entrances, crossroads, darkness, light, liminality, birth, death, mystery, herbs, and witchcraft. It was to her the dogs were sacrificed.

Hekate is often depicted with three bodies facing in different directions, which may symbolize the three realms she reigns over: Earth, sea, and sky. It could also represent her role in guiding those at a crossroads, or her ability to see into past, present, and future. Or that she is a triple goddess, representing Hekate, Demeter, and Persephone as one; grandmother, mother, and daughter.

I look out the window and watch the endless fields of grain, thinking about how they’re thousands of years old – eternal, even. This is the mystery I’m searching for.

We pass through pine groves and cross streams. Magnificent mountains begin to appear ahead of us, snow-capped.

I get off the train south of Figueres, where my accommodation is across from the village’s only restaurant. Everyone greets each other as they enter. They even greet me, out of place as I am. It’s filled with farmworkers and older men who were once farmworkers.

As I look around the room I wonder if any of these farmers’ ancestors lived at Mas Castellar de Pontós. If they drank the Kykeon at the temple there.

I wonder where its inhabitants went when the site was abandoned at the turn of the 2nd century BC.

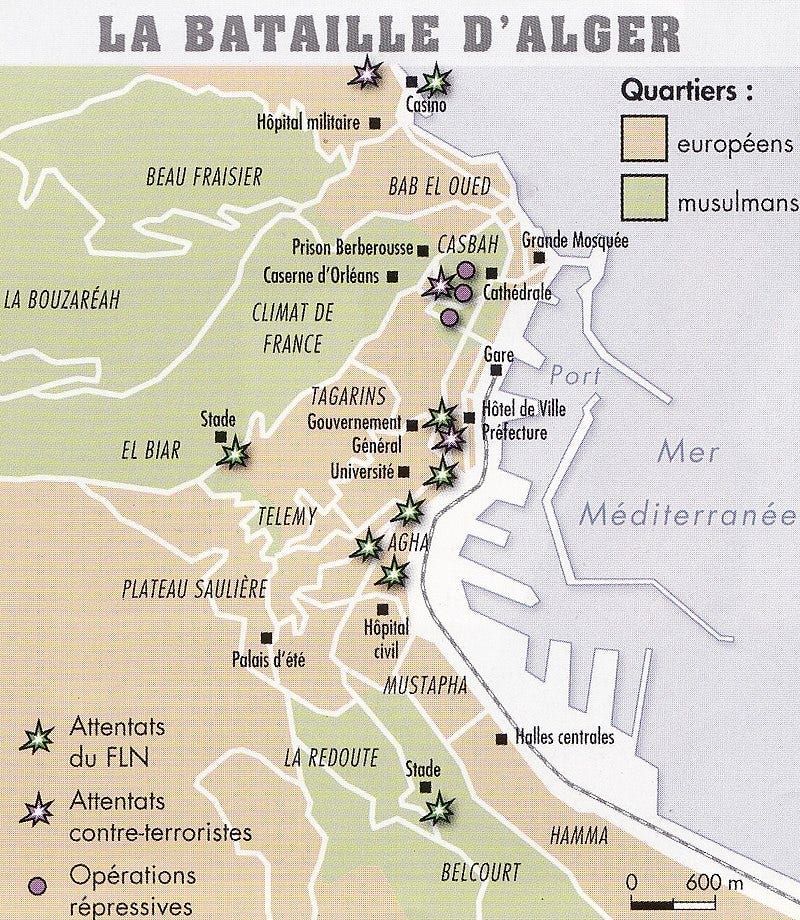

Did the Romans destroy the settlement as part of their crackdown on the Dionysian Mysteries in 186 BC?

Did the priestesses sacrifice dogs to Hekate for protection before fleeing to the Pyrenees?

The Dionysian Mysteries

The Dionysian Mysteries (or Bacchanalia) was the Mystery of the cult of the god of wine. They were known to meet outdoors, performing their rituals in the mountains where all initiates – regardless of their status in Greek society – became equal, creating an ethos of communitas. The maenads, or priestesses of Dionysus, mixed their wine with god knows what else. The sacrament was equivalent to the god – by drinking it, initiates became one with Dionysus. Music and ecstactic dance were also used to induce trance states. Welcoming everyone, including outlaws, the cult of Dionysus apparently became a hotbed of political radicalism. The Roman senate deemed the cult a threat to state security and issued an decree in 186 BC to outlaw it and its Mysteries throughout Italy. Dionysian temples were destroyed across the peninsula, and thousands of priests and initiates into the cult of Dionysus were put to death.

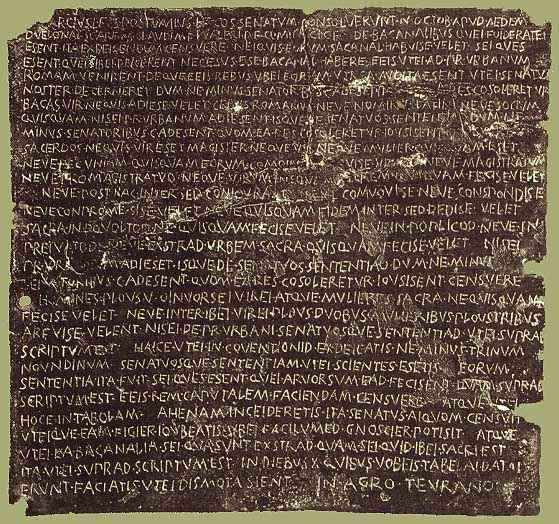

Senatus consultum de Bacchanalibus

Senatus consultum de Bacchanalibus

“No man is to be a priest; no one, either man or woman, is to be an officer (to manage the temporal affairs of the organization); nor is anyone of them to have charge of a common treasury; no one shall appoint either man or woman to be master or to act as master; henceforth they shall not form conspiracies among themselves, stir up any disorder, make mutual promises or agreements, or interchange pledges; no one shall observe the sacred rites either in public or private or outside the city, unless he comes to the praetor urbanus, and he, in accordance with the opinion of the senate, expressed when no less than 100 senators are present at the discussion, shall have given leave.”

The many figurines and incense burners found bearing the likeness of Demeter or Persephone at the temple at Mas Castellar de Pontós, and a psychedelic sacrament mixed in beer rather than wine, suggest the rites practiced there were an adaptation of the Eleusinian Mysteries – the mystery of the cult of Demeter, not Dionysus. But would the Romans have known the difference? And it was just around this time that the Romans were beginning to settle in the province now known as Alt Empordà.

The Eleusinian Mysteries

The Eleusinian Mysteries were the most famous – and secretive – mystery cult of the ancient world. Symbolized by an ear of grain, they were known for bestowing knowledge of immortality on their initiates and making them “better in every way.” Hundreds or perhaps thousands traveled to Athens to take part in the Mysteries every year for over a millennia. From Athens, they embarked on a 10 day pilgrimage to Eleusis, reenacting the story of Demeter, the Earth goddess, in her search for her daughter Persephone, goddess of the underworld and the Spring.

Once in Eleusis, before entering Demeter’s temple, the Telesterion, initiates would drink a sacrament called Kykeon. In the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, the goddess gives the recipe: barley, water, and pennyroyal. However given the transformational nature of the Mysteries – after which initiates became “god-like” and no longer feared death – it’s long been suspected that an entheogen was in the mix.

The 1979 book The Road to Eleusis proposed that the secret ingredient in Kykeon was ergot, a purple fungus that grows on the ends of grain, from which Albert Hofmann synthesized LSD. Ergot is poisonous, and it will kill you if prepared in the wrong way, but Hofmann concluded that the ancient Greeks could have removed its toxic compounds using an oil extraction method.

It’s a two hour walk from here to the archaeological site, but cutting across fields and highways isn’t always straightforward, and it takes me three. I say a short prayer on my way to the goddesses I’m about to visit.

Across the highway there’s a forest, and I’m invigorated by the peaceful cover of pine trees. I pick up my pace as the light begins to fade from the sky.

The breadbasket of Alt Empordà

Finally I come across the entrance to the site. As I walk up the path a tractor passes carrying farmwood. There’s an old farmhouse with a garden. A kitten poses for my camera, and a bull takes me by surprise, staring me down as I walk past.

Bulls were associated with Dionysus, but they were also sacred to Hekate. She was goddess of the night sky, and their horns, turned sideways, look like the crescent moon. In the Greek Magical Papyrii Hekate is referred to as “Bull-faced and bull-headed,” with “the eyes of bulls and the voice of dogs.” And in the Orphic Hymn to Hekate she is described as “drawn by a yoke of bulls.”

The Orphic Hymn to Hekate

I call Ækátî of the Crossroads, worshipped at the meeting of three paths, oh lovely one.

In the sky, earth, and sea, you are venerated in your saffron-colored robes.

Funereal Daimôn, celebrating among the souls of those who have passed.

Persian, fond of deserted places, you delight in deer.

Goddess of night, protectress of dogs, invincible Queen.

Drawn by a yoke of bulls, you are the queen who holds the keys to all the Kózmos.

Commander, Nýmphi, nurturer of children, you who haunt the mountains.

Pray, Maiden, attend our hallowed rituals;

Be forever gracious to your mystic herdsman and rejoice in our gifts of incense.

The settlement at Mas Castellar de Pontós was more than just a temple. The town was the “breadbasket” of Greek Catalonia, supplying grain to the nearby coastal cities of Empúries and Rhode. The lead archaeologist of the site, Enriqueta Pons, has estimated that as many as 2500 grain silos remain unearthed in a few hectares surrounding the main structures.

So it makes sense that they would have worshipped the agricultural goddesses Demeter and Persephone here and even, on the edges of the Hellenistic world, carried out an Iberian version of their Mysteries.

The remains at Mas Castellar

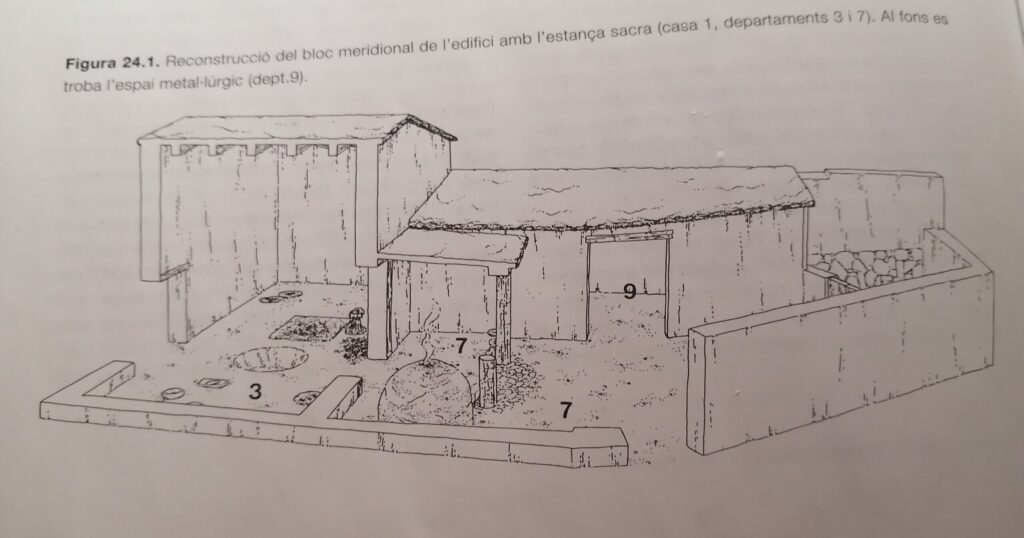

At the back of the site, two houses from the 2nd and 3rd centuries BC have been excavated. Room 3 of House 1 is a sort of temple, or what the archaeologists call a “domestic chapel” – a temple within a house, which was typical in ancient Iberian communities.

In the center of Room 3 they found an altar made of Pentelic marble, imported from Greece. Incisions in the marble and organic analysis indicate that it was used to make bloody sacrifices. The charred remains of several dogs were found in pits next to the altar. In front of the altar was a shallow water pit, probably used for ritual purification or ablution, or possibly to create steam baths.

The archaeologists found an incense burner in the shape of a woman’s face, representing Demeter or Persephone. Several like it were also found buried near the site.

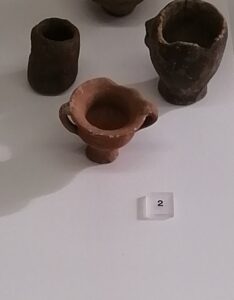

And strewn across the temple were 11 miniature chalices.

In the 1990s, the archaeobotanist Jordi Juan-Tresserras examined the remains at Mas Castellar with new technology that allowed for the detection of millennia-old organic compounds. He discovered remnants of pine and cedar in the incense burner.

And in one of the miniature chalices he found traces of “ergotized beer.” He also detected ergot in the teeth of a standalone jawbone from an adjacent room. The same ergot Albert Hofmann used to synthesize LSD, and that he hypothesized had been used in the Mysteries.

Tresserras knew what he had found, even if no one noticed for 20 years, until Brian Muraresku published his findings in his book The Immortality Key, which makes the case for a psychedelic sacrament in early Christianity. But Tresserras’s finding is the smoking gun, the holy grail – hard evidence that initiates in the Greek Mysteries were tripping on an LSD-like alkaloid.

While the other archaeologists speculated that this was the site of a grain cult, and more specifically the worship of Demeter and Persephone, in the 600 page monograph on Mas Castellar de Pontós published in 2002, Tresserras is the only one to bring up the Mysteries – or Hekate.

Tresserras cites The Road to Eleusis, and suggests the ergotized beer is the same Kykeon that was taken in the Eleusinian Mysteries, and that the people of Mas Castellar were practicing an Iberian version of them.

Subterranean votive silo

In 1992, archaeologists discovered an underground silo not far from the site’s main structures that contained not grain nor waste, but offerings. A fire had been made in the pit, and votive offerings were carefully placed upon the ashes. They found a terracotta head with a feminine face, nine amphora, agricultural tools, and domestic objects including keys. The fact that the offerings were buried suggests that they were left for a chthonic deity like Persephone – or perhaps Hekate.

Hekate in the Mysteries

The Eleusinian Mysteries are known as the cult of Demeter and Persephone, but Hekate has a prominent role in their myth. In the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, she is the only deity who comes to Demeter’s aid. Torches in hand, she leads Demeter to the sun god Helios, who tells the goddess that Hades has abducted her daughter with the permission of Zeus. When mother and daughter are finally reunited, Hekate is there to celebrate with them. She becomes Persephone’s guide, escorting her back and forth from the underworld each year, and takes Persephone’s place as Queen of the Dead when the maiden is above ground with her mother. Hekate was also recognized in the ceremonies at Eleusis, where initiates carried torches in her honor.

Tresserras suggests the keys found in the votive silo were offerings to Hekate, symbolic of her keys to the underworld and other realms, and her protective role as the guardian of entrances.

He also connects the dog sacrifices to Hekate, detailing many instances of dog sacrifice across the Greco-Roman world.

When I go back to read the monograph after my trip, I discover that Tresserras describes Hekate as carrying two torches – and accompanied by two howling dogs.

Hekate’s dogs

So I’m sitting in this ancient temple of a room where they sacrificed dogs and drank Kykeon. I feel at one with my surroundings; I begin to blend in with them. Until I flip my camera, and I notice how I’ve aged since the pandemic began, and all the rest before it. An existential anxiety creeps in – what am I doing here? The sun is going down, I’m feeling fragile, and I have to start walking back.

Out of nowhere, a dog runs up to me. She jumps on me, trying to lick me. I’m not a dog person, and I can’t remember the last time a dog has been friendly with me. In my experience, Spanish dogs are reserved with strangers. I ask her what she’s doing in this temple, a site of ritual dog sacrifice, and she digs furiously at the ground in front of me. I call her “Gosso,” from the Catalan word for dog. Her joy is infectious, and before I know it I’m laughing with her. It’s as if she’s come to comfort me, and to remind me that this is the point of life.

Gosso waits for me to depart, and I’m glad to have a companion. Walking past the farm again, now there are four bulls. Standing in a row, their heads are turned at the same angle, and they’re all watching me with equal intensity. But they don’t make me so nervous this time, because I have a protectress.

Two guides

Gosso meets up with her friend, and they begin chasing each other through the fields, unbridled in their happiness.

I turn to take the road into town, and they follow me. Luckily, cars are few, and Gosso begins to heed me as she and her friend guide me along the road to the town, occasionally disappearing from sight to frolic in the sunset.

Nightfall descends as we come upon the town of Pontós. The sound of sheep bleating comes from a nearby stable, and the dogs make our presence known as the lanterns light up the tiny, medieval village. I look for its only restaurant.

As soon as I find it, a car pulls up in front of us and a man gets out.

“Did they follow you?” he asks me.

Gosso doesn’t want to leave; she lies down in front of the restaurant in protest. The man picks her up and carries her back to his car.

Bolivian energy

I call a taxi and a Bolivian man arrives from Figueres and takes me back through the valley, lights sparkling about us in the night, the sensation of flying. Bolivia makes me think of lithium mining and the 2019 coup d’etat that ousted Evo Morales. And I think of how the energy carrying me and manifesting as light around me has been mined from the Earth. I think of how Morales returned from exile and Jeanine Añez was jailed. A victory for Bolivia’s indigenous peoples and the Earth. A rare glimmer of hope in a world growing dark.

Hekate as the feminine principle

I felt Hekate was with me, guiding me during this journey, bringing me safely to my destination.

Back at the villa I sit in the garden, looking up at the starry night sky that is Hekate’s domain. I could feel her presence with me still, looking down from the heavens.

My experience with Hekate reaffirmed my belief in communism and put it in an ancient, feminist, Earth-based context. As triple goddess over all realms, dark and mysterious but carrying torches, Hekate is Yin, the feminine principle.

Hekate is at once a goddess of the underworld, the heavens, the Earth and the sea. Her priestesses Medea and Circe have been portrayed as wicked witches. However in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, her role is totally benevolent. And in the Chaldean Oracles, a neoplatonic poem (Plato himself was deeply influenced by the Eleusinian Mysteries), Hekate is the World Soul, and the guardian between the spiritual and physical realms.

The Earth goddess Demeter and her daughter Persephone are also aspects of Yin, though Hekate encompasses both of them. As in the Eleusinian Mysteries, these goddesses remind us that we live by the Earth. In traditional societies, like the simple farming community at Mas Castellar, what we took from the Earth served to sustain us more or less equally.

As society grew and became more complex, more was extracted. As long as what is taken from the Earth serves the good of all equally, it’s in balance. However evil men take more than their share, and use what they extract from Hekate’s realms and the toil of the working classes to create structures that secure their power and oppress those beneath them, destroying everything around them in a quest for power. Quo vadis? Ad quam finem?

This imbalance reaches an apex with nuclear weapons. Uranium is extracted from the Earth and the underworld, concentrated into the ultimate destructive force that’s wielded by men for the purpose of world domination. It’s a supreme expression of evil. An extreme disequilibrium and an affront to the feminine principle – extracting from her realms, poisoning and threatening to poison Earth, sea, and sky, and enslaving the world’s creatures to a gang of men who care for nothing except their own power – their power over women, other men, and the Earth itself.

Feminine justice

Hekate is an empowerer of women. Some of her followers, like Circe and Medea, take revenge on powerful men through witchcraft. Even Demeter brings the world to the brink of starvation in her grief. In doing so she spites the patriarchy and brings Zeus to his knees. It’s a feminine wrath, and sometimes necessary to restore balance.

In Essays on a Science of Mythology Carl Jung analyzes the myth of Demeter and Persephone. He concludes that the secret of the Eleusinian Mysteries was that we live eternally through reproduction. Hekate is Demeter and Demeter is Persephone. Mother and daughter are one, just as an ear of grain houses its descendents in seeds that fall to the ground, and is born again in Spring.

Carl Ruck, who coauthored The Road to Eleusis, suggests that inside the Telesterion, initiates witnessed Persephone return from the underworld to give birth to a child, Dionysus.

We live on through the Earth. We are born of the Earth, we return to the Earth, through this cycle we give life to plants and other creatures.

It follows that our existence depends on the Earth and our care of it. If we hurt her, she may just starve us all. Balance, respect for nature, and respect for the feminine is necessary for life to continue, for this organic immortality, to live eternally.

In his book, Muraresku describes how the Roman hierophant Praetextatus intervened when the Roman emperor Valentinian sought to shut down the Eleusinian Mysteries in 364 AD. He told Valentinian that the Mysteries “hold the human race together” and that their loss “would make the life for the Greeks unlivable.”

At the end of the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, Rhea comes to summon Demeter to Olympus. Before setting off, the goddess makes the world fertile again, and teaches the secrets of her rites to priests in Eleusis:

“Straightaway she sent up the harvest from the land with its rich clods of earth. And all the wide earth with leaves and blossoms was laden. Then she went to the kings, administrators of themistes, and she showed them—to Triptolemos, to Diokles, driver of horses, to powerful Eumolpos and to Keleos, leader of the people [lâoi]—she revealed to them the way to perform the sacred rites, and she pointed out the ritual to all of them—the holy ritual, which it is not at all possible to ignore, to find out about, or to speak out. The great awe of the gods holds back any speaking out. Blessed [olbios] among earth-bound mortals is he who has seen these things.

But whoever is uninitiated in the rites, whoever takes no part in them, will never get a share [aisa] of those sorts of things [that the initiated get], once they die, down below in the dank realms of mist.”

If we properly worship Demeter (the Earth) we will be reborn. If not, we die. Hekate is here to guide us towards this worship, to help us find each other, and in doing so be renewed and transformed. I believe she guides women to come into their own power.

She has the keys to unlock our cages, she knows the plants that make us fly, her dogs protect us, and her torches light the way.

Sources

Betz, H. D. (Ed.). (1996). The Greek magical papyri in translation, including the demotic spells, volume 1 (Vol. 1). University of Chicago Press.

Juan Tresserras, J. (2000). La arqueologia de las drogas en la peninsula iberica. Complutum (Madrid), No. 11, Ene.-dic. 2000, P. 261-274.

Kallímakhos. 2010. The Orphic Hymn to Hekate. HellenicGods.org. https://www.hellenicgods.org/the-orphic-hymn-to-hecate-aekati—hekate

Muraresku B. & Hancock G. (2020). The immortality key : the secret history of the religion with no name. St. Martin’s Press.

Oberhelman, S. M. (Ed.). (2013). Dreams, healing, and medicine in Greece: from antiquity to the present. Ashgate Publishing Company.

Pons, E. (2002). Mas castellar de pontós (alt empordà): un complex arqueològic d’època ibèrica (excavacions 1990-1998). (Ser. Sèrie monogràfica / museu d’arqueologia de catalunya, 21). Generalitat de Catalunya, Departament de Cultura. P. 548-556.

Taylor-Perry, R. (2003). The god who comes : dionysian mysteries revisited. Algora Pub.

Wasson, R. G., Hofmann, A., & Ruck, C. A. P. (2008). The road to eleusis: unveiling the secret of the mysteries (30th anniversary). North Atlantic Books.

In January, the senate overrode a veto to pass a

In January, the senate overrode a veto to pass a