Spectres of post-colonial Algeria

Hauntology & silence in the deserts of the heart

By McBond

« Il fallait quelqu’un pour exprimer ce silence, lui faire rendre tout ce qu’elle contenait de tristesse, pour ainsi dire la faire chanter. »

“Someone had to express this silence, make it give back everything it contained in sadness, so to speak and make it sing.”

– Marguerite Yourcenar, Alexis, ou le Vain Combat.

Three squirrels skipped across a sodden lawn bilious-green under a grey Saturday sky in Lanarkshire. The house of the Society of Missionaries of the Venerable Geronimo seemed hunched down on top of a hill beneath the Cathkin Braes.

Twenty-six years earlier Bartholomew McCorquodale had been ordained in a nearby Catholic parish, in July 1993.

The bishop was lucid for the occasion, and there’s a picture of McCorquodale in the habit of the Society of Missionaries of the Venerable Geronimo going into St Finbarr’s church hall. Boxy 1990s cars in the background. He was trussed up like aspahi in a borrowed burnous.

The cardinal who founded the Society in 1868 must have seen the locally recruited spahis of the French colonial army in Algeria: did this inspire his choice for the habit of the Missionaries of St Geronimo? McCorquodale’s own military experience was limited to the Glasgow University Officers’ Training Corps — mornings on drizzly ranges firing off a few desultory rounds from the Sterling submachine gun and the Belgian-designed SLR — but he would later encounter clerics who had served in the French army, and who had retained something of a martial snap.

McCorquodale had recently heard of a now-deceased French priest who returned to Algeria after independence in 1962 to atone for his misdeeds as a French paratrooper during the Algerian independence struggle of the 1950s.

A few weeks prior to his ordination he had some cards printed in Toulouse — where he had completed his seminary studies — with a reproduction of a fourth-century Ravenna mosaic of the prophet Jonah being vomited out of the whale. The card was presently in one of his notebooks at an art gallery in Carthage, so he was recalling its details from memory.

Algiers, still a site of war

Just over two months later — September 1993 — he arrived in Algiers via Toulouse with little idea of the gravity of the situation. The conflict between the Algerian state and Islamist extremists had been background noise in the French media since early 1992. Two French surveyors had been assassinated in September 1993. He did not recall receiving any particular words of caution or guidance from the Missionaries of the Venerable Geronimo about the situation in Algeria.

In his Journal d’Algérie (2003) the photographer Michael von Graffenried mentions a figure of 700 Islamists killed between summer 1992 and October 1993, 400 members of the security forces, while 10,000 political activists were held in detention camps. Graffenried gives a figure of 140 “random” murders over the same period.

A Swiss confrère had attended McCorquodale’s ordination in July, and seemed more concerned about the need for lines of demarcation between his future activities and those of a pugnacious French member — let’s call him “the Duke’’– of the Saharan community for which he was destined. The Algerian embassy in London dealt with McCorquodale’s tourist visa application by post, no questions asked.

In his Journal d’Algérie (2003) the photographer Michael von Graffenried mentions a figure of 700 Islamists killed between summer 1992 and October 1993, as well as 400 members of the security forces, while 10,000 political activists were held in detention camps. Graffenried gives a figure of 140 “random” murders over the same period.

The Society’s regional house in Algiers was in the Rue des Fusillés in the Belcourt area of Algiers, not far from Albert Camus’s birthplace. A large colonial-era street map of Algiers hung on the wall near the refectory, its wooden frame seeking to corral an unruly reality.

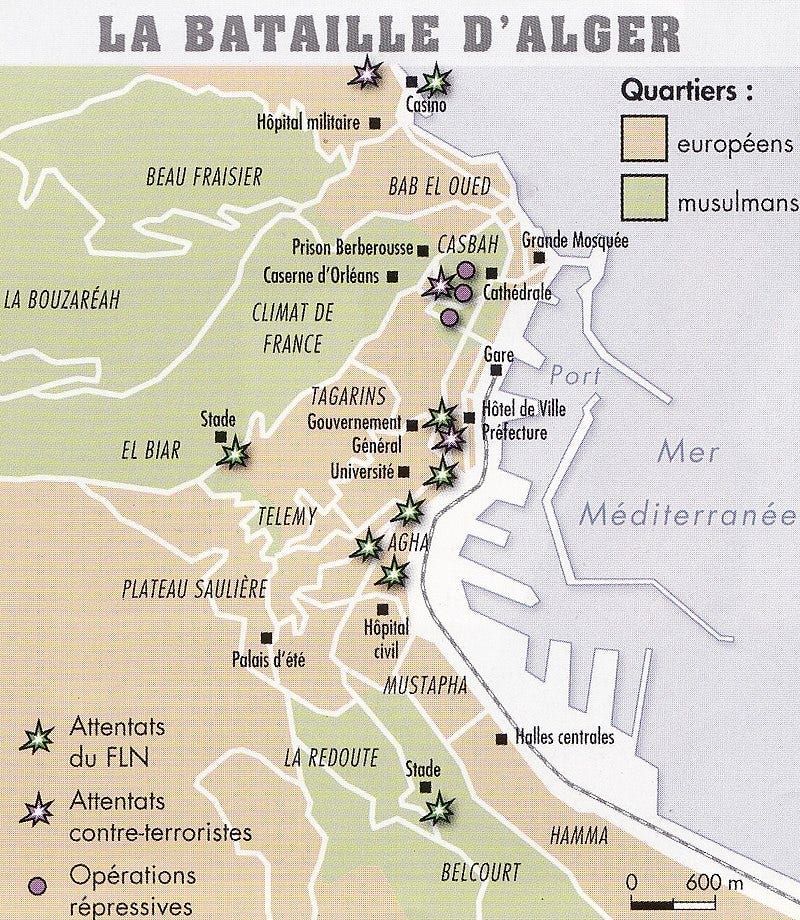

The same map, printed in the 1950s, appears from time to time in Gillo Pontecorvo’s 1965 film The Battle of Algiers. French military officers in the film use the map to plan their campaign against the FLN in 1957. There’s a similar map in Julien Duvivier’s 1937 film Pépé le Moko. The street names on these kinds of maps included those of French military mass murderers of the 1840s and 1850s: Cavaignac, Pelissier, Bugeaud — specialists in organized pillage and asphyxiation (by smoke) of hundreds of indigenous fugitives in the grotto of Kabylia. A haunted haunting map.

The atmosphere in Rue des Fusilles was, however, cordial.

After some jovial remarks, the then-Regional Miguel Larburu asked if he had drafted his last Will and Testament. Friar Georges Bergantz had the courtly manners of a fencing-master, while the taciturn Friar Saffroy had, McCorquodale would later learn, compiled a chronology of the Touat region of southwest Algeria.

This initial stay in Algiers lasted but a few days and was marked only by a somewhat comical incident in which McCorquodale and his Swiss colleague accidentally drove onto the runway at Algiers airport, passing within 100 metres of a stationary Boeing while retrieving from Air Freight a green tin trunk — similar to those in photographs of missionary “caravans” circa 1890 — containing his baggage sent from Toulouse.

Atlantis and the Sahara

The term “the South” had a special aura among the Missionaries of the Venerable Geronimo at that time, summoning up images of Saharan sand dunes, camel caravans shimmering in a heat haze, while Charles de Foucauld — soldier turned desert contemplative — meditated in his Tamanrasset fastness. The South was seen as removed from the tensions of northern Algeria, both in the pre-1962 period of French occupation and in the decades thereafter until the 1990s.

A few days later they set out in a white Renault 4 for Ghardaïa, 600 kilometres away, heading southwards.

Until the 1960s the Sahara had been a separate territory for the Missionaries of the Venerable Geronimo, with around 50 priests and brothers involved in education and professional training as well as pastoral activities among the French civilian and military population of the Sahara.

The vision of an idealized Saharan landscape had been crafted over a lengthy period. In the late nineteenth century the Touareg nomads were reinvented by French scribes as noble lords of the desert with hazy links to Christianity and northern races.

The lost city of Atlantis was reputedly located in the far Sahara, and gave its name to the main hotel in Gao in northern Mali where McCorquodale had sojourned from 1988-1990. He thought of Atlantis and the eponymous 1919 novel L’Atlantide with its mysterious desert queen Antinea loosely modelled on a fourth century figure of Touareg folklore. While in Namur a few weeks before, he had seen that Antinea was the brand name for a range of lingerie.

A landscape of ghosts and silence

Moving south towards Ghardaïa there were however traces of a darker past: old French watchtowers from the 1950s in the mountains pressed back into service by the Algerian army, and earlier constructions used as observation or heliographic posts as the French pushed southwards into the Sahara in the mid-nineteenth century. They passed through Laghouat en route to Ghardaïa. Laghouat was the oasis city where the Catholic bishop of the Sahara resided— a restless, rangy Canadian named Michel Gagnon, who had arrived in Algeria in 1958.

McCorquodale and his fellow-missionary were following the route taken by French forces moving southwards from the coastal territories occupied by France in 1830. French forces occupied Laghouat in a particularly violent assault in November 1852. 2,500 people were killed and the year is still remembered as “sanat- al-khlā’”or the “year of desolation”. French military eyewitnesses describe crazed soldiers bayoneting civilians indiscriminately.

The artist Eugène Fromentin travelled through Laghouat in 1853 and hisUn été dans le Sahara (A Summer in the Sahara, 1858) is haunted during its Laghouat passages by phantasms of the slaughter of the previous year.

Bullet-riddled doors, crowds of beggars, and half-buried corpses were tangible traces of carnage by which Fromentin seems psychologically scarred.

At the time, McCorquodale had little awareness of Laghouat’s violent past as an “assassinated city” (to use Fromentin’s expression), and his Swiss colleague preferred to “live in the present”. Other clerics would recount how they had singlehandedly won the battle of Monte Cassino in 1944. Radio silence generally prevailed on matters surrounding colonial Algeria.

While silence had often been characteristic of clerical life in McCorquodale’s experience, there were, he thought, particular reasons for postcolonial opacity among the mainly French clerics in 1990s Algeria.

A small number may have been unable to “process” episodes from the Algerian War (1954–1962). Were individual missionaries as enthusiastic for the Algerian national cause as later missionary historians would claim? How divided were communities over the course of events as Algeria moved to independence in 1962?

McCorquodale’s studies in Toulouse had alerted him to scholarly work on colonial history and memory by figures such as Benjamin Stora, although this was still in an incipient phase. He recalled films such as Indochine, where colonialism was seen through the lenses of romance and glamour.

Hauntology and the mysteries of Algiers

The Algerian-born philosopher Jacques Derrida (1930–2004) would introduce his concept in 1994 of hantologie, a “puncept” coined to make a play between things that can be said to exist and things that cannot, but nonetheless appear, haunting reminders of lingering trouble.

One can be haunted backwards by things that no longer exist but still have impact, the ghosts of history — the map in Rue des Fusillés, for example — as well as by ghosts of an unrealised future, such as a soon-to-be demolished Brutalist structure from the 1980s. Perhaps the missionaries McCorquodale encountered were themselves haunted by the cancelled future of the optimistic nation building of the 1960s and 1970s, with which they and the wider Catholic community had been in solidarity.

The tin-can Renault rattled southwards beneath blue skies and a rocky salmon-pink landscape. They could not have foreseen how events would spiral out of control in a landscape haunted by memories of past violence. McCorquodale recalled that he had with him a copy of Robert Irwin’s novel The Mysteries of Algiers.

The novel begins in the Sahara during the Algerian war of independence. Philippe Roussel, a French intelligence officer, veteran of Indochina and prisoner of the Vietminh, has transferred his loyalties to Communism and is working as an anti-French agent. Unmasked in the Saharan post of Fort Tiberias, Roussel takes flight, eliminating anyone who stands in his way, passing through Laghouat on his mayhem-strewn progress towards Algiers.

Robert Irwin is a specialist in the Arabian Nights, and The Mysteries of Algiers is peopled by deranged genies. McCorquodale recalled later meeting a Catholic monk in Algiers coincidentally called Philippe — an ex-officer in the French army who revealed that his father had fought on the Eastern Front in the Second World War in the Legion of anti-Bolshevik Volunteers alongside the Germans. Irwin’s novel describes with particular relish the “Children of Vercingetorix”, a right-wing activist group of murderous tendencies who invoke the “God of the Franks”.

The sounding of the gong for lunch interrupted McCorquodale’s reminiscences. The mist was lifting over the Cathkin Braes. The Mysteries of Algiers had taught McCorquodale that things are not always what they seem.

Not a bad way, he thought of engaging with the opacity and silence of what W.H. Auden calls the deserts of the heart.

24/11/19

With the farming of a verse

Make a vineyard of the curse,

Sing of human unsuccess

In a rapture of distress;

In the deserts of the heart

Let the healing fountain start,

In the prison of his days

Teach the free man how to praise.

W.H. Auden

“God is gathering us out of all regions till he can make resurrection of our own hearts from the very earth, and teach us that we are all of one substance, and members of one another. For the one who loves his neighbor loves God, and the one who loves God, loves his own soul.”

– St. Anthony of the Desert

“The person who abides in solitude and quiet is delivered from fighting three battles: hearing, speech, and sight. Then there remains one battle to fight-the battle of the heart.”

– St. Anthony of the Desert

“Learn to love humility, for it will cover all your sins. All sins are repulsive before God, but the most repulsive of all is pride of the heart. Do not consider yourself learned and wise; otherwise, all your efforts will be destroyed, and your boat will reach the harbor empty. If you have great authority, do not threaten anyone with death. Know that, according to nature, you too are susceptible to death, and that every soul sheds its body as its final garment.

– St. Anthony of the Desert

“A time is coming when men will go mad, and when they see someone who is not mad, they will attack him, saying, ‘You are mad; you are not like us.'”

– St. Anthony of the Desert

“It is interesting too that, in all the religious traditions, deserts and places where there is a minimum of sensory stimulation have always been regarded in an ambivalent way, first of all as the places where God is nearest and secondly as the place where devils abound.”

– Aldous Huxley