Psyche, Jung, LSD, & transformation

The word psyche means soul in Greek, as well as butterfly. Psyche (or Psyke) is also the goddess of the soul.

The butterfly emerges from its dead shell as a new being. Perhaps our souls do the same when we part from this world, or when we undergo a transformation. However what goes on inside the cocoon – how the caterpillar disintegrates and reconstitutes itself in an entirely new form – is a mystery.

Psyche the mortal

Like the butterfly, the myth of Psyche is transformational. She was a princess, and so beautiful that some began to worship her instead of Aphrodite. Jealous, the goddess of beauty sent her son Eros (Cupid), to sabotage Psyche.

Eros, the god of love, can make anyone fall in love with his arrows. And so Aphrodite instructed him to shoot Psyche ao she would fall in love with a hideous beast. Instead, he accidentally scratches himself with his own arrow and falls deeply in love with Psyche, disobeying his mother.

Meanwhile, Psyche has had no luck finding love or a husband. So her father goes to consult the god Apollo, who condemns her to marry a violent dragon. She jumps from a cliff to escape (or meet) her fate, but is instead safely carried by a wind spirit to a beautiful palace.

Psyche is met by a lover at night, but he won’t let her see him. Convinced he’s a monster, she eventually confronts him with a lamp. She’s startled upon seeing Eros, and brushes against one of his arrows, instantly falling in love with him. In her surprise she drops her oil lamp on Eros. Injured, he wakes up and flees. Psyche goes after him.

In her search, Psyche runs into Pan and Demeter, but they cannot help her against Aphrodite. She realizes that she must go to see the angry goddess, who subjects her to torture and impossible tests. However nature conspires to help her; an army of ants spontaneously lends her their aid, and Zeus himself intervenes in the form of an eagle to save her. Finally, Psyche is told to go to the underworld to retrieve a gift from Persephone for Aphrodite. She again tries to commit suicide, when the very tower she would jump from speaks to her, giving her instructions for safe passage to the underworld and back.

Psyche, the goddess of the soul

Upon her return from the underworld, Psyche is reunited with Eros. Zeus gives her ambrosia, turning her into a goddess, and she becomes the goddess of the soul. Zeus then presides over the sacred marriage of Psyche and Eros, the union between soul and love. Their story is told in Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

At every turn, just as Psyche is about to die, nature saves her. Why does nature favor her?

We are left to think of Psyche as somehow virtuous and blessed. She is motivated in her journey by her love for Eros. Her suicide attempts show her despair at her forbidden love, and that she is more willing to shed her mortal skin than suffer Aphrodite’s despotism or risk her soul in the underworld. She is in this sense pure; true to herself.

Nature recognizes and supports goodness, sometimes even cosmically intervening in our own folly. Her journey and her visit to the underworld are also metaphors for how traumatic experiences, taking risks, despair, and going to dark places are often a part of our transformation. By trusting nature, going towards love, and refusing to live on others’ terms, instead of dying, Psyche is transformed into a goddess.

The soul, butterflies, and neuroscience?

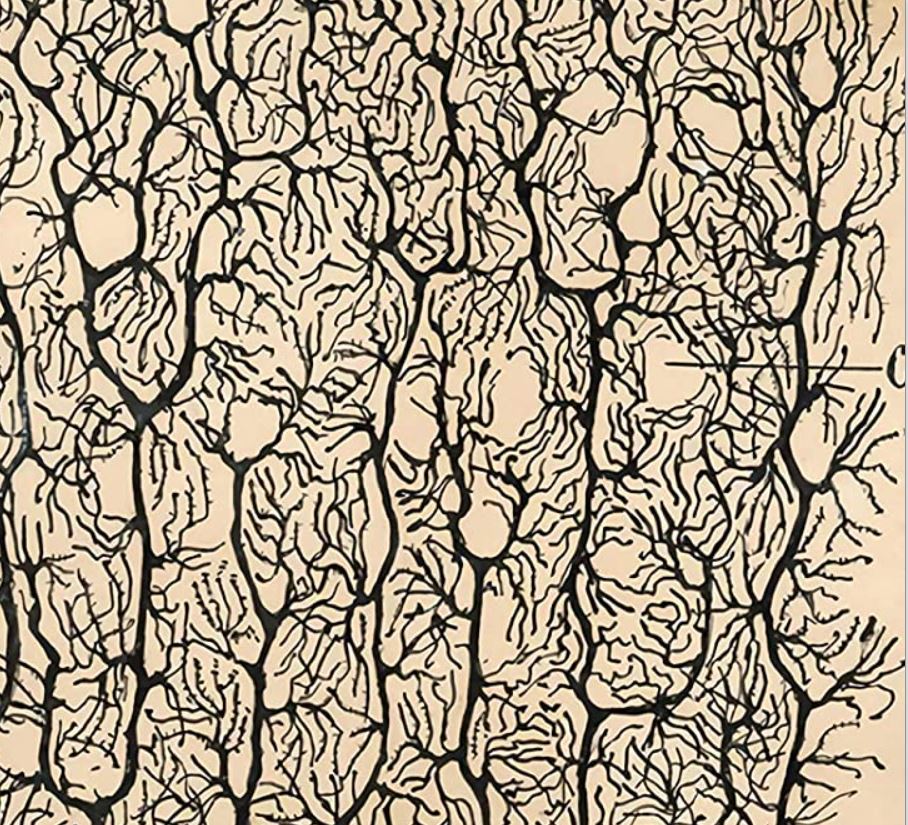

The modern father of neuroscience, Santiago Ramón y Cajal took up the symbolism of the soul and butterflies two millenia later to describe neurons. His work drawing neurons and interneurons won him more fame and recognition.

“I felt at that time the most lively curiosity, somehow romantic, for the enigmatic organization of the organ of the soul. Humans, I said to myself, reign over Nature through the architectural perfection of their brains…To know the brain, I told myself in my idealistic enthusiasm, is equivalent to discovering the material course of thought and will…Like the entomologist hunting for brightly colored butterflies, my attention was drawn to the flower garden of the grey matter, which contained cells with delicate and elegant forms, the mysterious butterflies of the soul, the beating of whose wings may someday (who knows?) clarify the secret of mental life…”

Santiago Ramon y Cajal was right; thought is created by brain activity. Neurotransmitters activate synapses, which then relay a message through a small electrical signal that travels along the neuron’s axon, activating a cascade of downstream synapses, producing thoughts. These thoughts then shape how we see ourselves and the world.

We’re discovering how the mind works, and this is opening our psyches up to new possibilities. Ideas flitter like brightly colored neurotransmitters at a synapse; catch them.

Since science is useful in explaining and predicting physical phenomena, we’ve been conditioned to accept it as universal truth. However it isn’t the only way of knowing the world.

Antiquity may have understood the world differently, but many myths survive because they continue to offer insight. Neuroscience is exciting to understand, if tricky and even dangerous to manipulate. And the 20th century offers us yet another perennial understanding of ourselves.

The Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung distinguished the psyche from the soul, which he understood as the expression of personality. He defined the psyche as “the totality of all psychic processes, conscious as well as unconscious.”

Jung was very critical of the growing materialist, “scientific” trends in psychology. While Santiago Ramón y Cajal was busy searching for it, Jung insisted that even though it couldn’t be seen, the psyche is the most amazing and important thing in the world, saying:

“I am of the opinion that the psyche is the most tremendous fact of human life. Indeed, it is the mother of all human facts, of civilization and its destroyer, war.”

Transformation is a recurrent theme throughout Jung’s works. In Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious he devotes a chapter to rebirth, describing a few scenarios in which it can take place: transmigration and reincarnation (there’s a subtle difference), transmutation (becoming something else entirely, as when Psyche went from mortal to goddess), and psychological renewal and rebirth (the most common form).

However, change needn’t always be positive. In Greek mythology, beautiful women are transformed into monsters as well as goddesses. Jung refers to a South American tradition in which depression is described as a “loss of soul”. Similarly, he describes the anxiety following shock or trauma as “abaissement”, in which the personality “shrinks”. The descriptions feel apt. This is contrasted with the positive transformation we seek, which he calls an “enlargement of personality”.

“Rebirth… suggests the idea of renovatio, renewal, or even of improvement brought about by magical means. Rebirth may be a renewal without any change of being, inasmuch as the personality which is renewed is not changed in its essential nature, but… parts of the personality, are subjected to healing, strengthening, or improvement. Thus even bodily ills may be healed through rebirth ceremonies.”

Jung elaborates on the different means by which a transformation or “rebirth” may occur.

Rituals as common as communion at Catholic mass can give rise to renewal, he says, though he theorizes that crowds diminish the power of rituals in accordance with their magnitude, and that this is why they must be repeated for their effects to be sustained. Techniques such as meditation or yoga may be used to induce transformation, and visionary or transcendental experiences can also provoke transformation.

The Eleusinian Mysteries

Among the examples of transformation he provides, Jung alludes to are the Eleusinian Mysteries, which connects perfectly to some of the experimental treatments we’re exploring in this journal.

An ancient psychedelic cult of Demeter, the goddess of harvest and grain, revealed to its initiates the secrets of life, death, and immortality. The guest list reads like a who’s who of the Greco-Roman world: Socrates, Plato, Plutarch, Marcus Aurelius, and Cicero all are said to have participated in this rite, which took place annually over the course of 1,500 years.

The initiates would journey to Eleusis, where Demeter was offered comfort while looking for her daughter, Persephone, after she had disappeared to the underworld, reenacting Demeter’s search. Persephone’s eventual return marks the beginning of Spring. The sprouting of seeds of grain after the winter symbolizes immortality as the eternal continuity of life through generations.

Upon arriving in Eleusis, initiates drank a psychoactive brew made of barley and pennyroyal called Kykeon, and were said to come away with special knowledge of life after death.

Albert Hofmann, the chemist who discovered LSD, would go on to write a book purporting that the Eleusinians had, in fact, been ingesting LSD (or a very similar alkaloid). The theory is logical: Demeter is the goddess of the harvest and grain, and LSD is derived from ergot, a fungus that grows on barley and rye. Though ergot can be quite poisonous when accidentally ingested, apparently its entheogenic properties are water-soluble whereas its most toxic ones are not. So it’s possible that the priests of Eleusis had discovered how to prepare a beverage with ergot in just the right way, as Hofmann happened upon LSD some four thousand years later.

Traces of ergot were found at ruins of temples of Demeter and Persephone in Catalonia. These findings appear to confirm the theory that these ancient Greek philosophers were essentially taking acid (and that this tradition had spread to Greek colonies across the Mediterranean).

Initiates were sworn to secrecy about their experiences, but some secrets escaped. And some, perhaps, were disguised as myth. Plato’s Republic concludes with “The Myth of Er,” which tells the tale of a man who returns from the afterlife to share his knowledge with the living.

Er has seen the celestial planes of heaven, those returning from sentences in the underworld (where they must endure 10x the suffering they’ve inflicted upon others in their previous lives before being released), and how the newly dead choose their next lives as animals, good people, or powerful tyrants. Previous lives are forgotten with a drink from a river, and old souls go on to embark on new lives.

The Delphic priest and philosopher Plutarch described the revelations of the Eleusinian Mysteries in fewer words:

“Because of those sacred and faithful promises given in the mysteries… we hold it firmly for an undoubted truth that our soul is incorruptible and immortal. Let us behave ourselves accordingly.”

Transformation through love

Love is another way we can be transformed. Themes of rebirth and immortality are also prominent in Plato’s Symposium, where the intellectuals of Athens gather at a dinner party, each one delivering a speech on the god Eros, or the nature of love.

The most prominent account is that of a woman philosopher, Diotima. Though she isn’t at the party, Socrates credits her with teaching him the nature of love and recounts their conversation at the agora.

Diotima says love moves towards the beautiful, which is synonymous with the good. Moved by love, people are filled with the desire to give birth to more beauty, through reproduction or the creation of art, philosophy, and virtuous acts.

Eros, or love, represents longing, and begins with a sense of incompleteness in the self. Through love of the other, the incomplete, needy lover is redirected towards the world and inspired to create. Their vulnerability transforms them from an insecure being into a conduit for creativity. Love begets possibilities for creation and immortality in the form of children, works of art, noble acts, and wisdom and discourse, or, philosophy. Love generates change and creation, transforming both the creator and the world.

For Diotima, love is a process of becoming that is also generative, giving birth to new people, things, and ideas along the way. The final step in this transformation, however, is completely distinct from the process. It culminates in the knowledge and contemplation of beauty itself. Once a person has seen true beauty and is fully transformed by love, they lose interest in the mundane, and lack the inner restlessness that drives creation, she says. They’ve had a transcendental experience that persists, and are then complete, and content to contemplate the eternal beauty of the world in a state of ecstasy. Full metamorphosis, they become their own creation.

Journeying through madness

Socrates describes love in yet another way in the Symposium, which is also in a sense transformational:

“The madness of a man who, on seeing beauty here on earth, and being reminded of true beauty, becomes winged, and fluttering with eagerness to fly upwards, but unable to leave the ground, looks upwards like a bird, and takes no heed of things below—and that is what causes him to be regarded as mad.”

Here we’re reminded that transformation can also take us through or resemble madness, and that our transformations aren’t always accepted by others. It’s possible that we could become detached, or find ourselves emerging with a new identity or perspective not understood or shared by those around us.

Jung also recognizes the transformative power of madness – which is comforting to hear, now that we’ve all gone mad. Likening it to our shadow – or that part of ourselves which we reject, and therefore remains unconscious and unintegrated – he urges us to embrace it:

“Be silent and listen: have you recognized your madness and do you admit it? Have you noticed that all your foundations are completely mired in madness? Do you not want to recognize your madness and welcome it in a friendly manner? You wanted to accept everything. So accept madness too. Let the light of your madness shine, and it will suddenly dawn on you. Madness is not to be despised and not to be feared, but instead you should give it life…If you want to find paths, you should also not spurn madness, since it makes up such a great part of your nature… Be glad that you can recognize it, for you will thus avoid becoming its victim. Madness is a special form of the spirit and clings to all teachings and philosophies, but even more to daily life, since life itself is full of craziness and at bottom utterly illogical. Man strives toward reason only so that he can make rules for himself. Life itself has no rules. That is its mystery and its unknown law. What you call knowledge is an attempt to impose something comprehensible on life.”

Ancient Greece keeps circling back to Jung. It’s ironic that he makes reference to the Eleusinian Mysteries, because they hint at how nature may aid us again by allowing ordinary people to experience the sacred. Hofmann’s LSD theory of the Mysteries hadn’t yet been formulated, however psychedelics were just starting to be experimented with in the last decade of Jung’s life. In a letter, Jung expressed that he didn’t think regular people should take psychedelics. He believed that normal people wouldn’t be able to psychologically integrate such intense experiences, or that they wouldn’t be ready to receive the responsibility that would come with the knowledge they offered. However he elsewhere wrote that we are only able to know or become what we’re ready to receive or be.

Perhaps psychedelics aren’t for everyone. There are other means of transforming ourselves. And just like traumatic or psychedelic experiences, or Jung’s embraced madness, they have to be integrated into our psyches, whether through ritual, conversations, journaling, or daily practices like yoga or meditation.

However we’re transformed – through experience, ritual, yoga, drugs, psychedelics, a vision or an epiphany – experience belongs to people, not the elite whether they be philosophers or millionaires. Individual experiences must also drive cultural transformations.

The collective unconscious

For Jung, individuals were never – are never – islands. Equally important as our individual unconscious is his concept of the collective unconscious; that part of our psyches that is unconscious and shared by all of us – humanity as a species.

The collective unconscious according to Jung is visual, and composed of archetypes that have recurred throughout the thousands of generations of our species. It’s humanity’s common memory, evoking how the Eleusinians saw eternity in the fresh green fields of spring.

Archetypes are symbols. Many correspond to the roles we play in the course of our lives as humans. These archetypes are seen in Greek gods and goddesses and their stories, which individuals across time and cultures can relate to, and structure our understanding of the world.

Jung regards the collective unconscious as inherited, like instincts. Some instincts are ancient, though more recent ones may have reached us through epigenetics. For instance, trauma can leave markers on the genes of their offspring, and be passed down to the next generation. And socially, we repeat abusive behaviors that we’ve learned from others, perpetuating trauma against ourselves and others. Similarly, Jung theorizes that certain patterns and characters are repeated throughout humanity’s history and stored in the collective unconscious, whether it exists in our genes or our culture or both, which finds expression in stories and religious mythology.

Jung roots much modern neuroses in the absence of religious and mythological forces that express these archetypes, and condemns the efforts of psychiatry to individualize mental health problems:

“In numerous cases of neurosis the cause of the disturbance lies in the very fact that the psychic life of the patient lacks the co-operation of these motive forces. Nevertheless a purely personalistic psychology, by reducing everything to personal causes, tries its level best to deny the existence of archetypal motifs and even seeks to destroy them by personal analysis. I consider this a rather dangerous procedure which cannot be justified medically.”

He continues:

“Since neuroses are in most cases not just private concerns, but social phenomena, we must assume that archetypes are constellated in these cases too.”

The individualization of mental health

Jung was right to be skeptical of a psychology that reduces everything to personal causes. Most neuroses are social phenomena.

As the rich get richer and the poor get poorer, in a society where wealth equals power, we are necessarily disempowered. These symptoms are then pathologized and collectively called “mental illness”. As if it’s our fault for not being richer, and we all could be if we just tried hard enough. When we are threatened with eviction, underpaid, overworked, or undervalued because of our relative poverty, not only are our livelihoods under threat, but there is a very clear message being handed down: that we do not matter. This is a crucial, overlooked aspect of our collective mental health crisis.

At the same time, through the media, the very wealthy proclaim themselves our archetypal gods.

Similarly, a first step in overcoming the inferiority complexes transmitted to us by the media and a culture controlled by the wealthy is simply to reject these cultural values. We can start with a healthy disrespect. Don’t accept their measures of success, or who other people tell you who are. Be like Psyche – go towards what you love, and live life on your own terms.

While we need large-scale changes and solutions, one way of overcoming the precarity of our economic system and its associated stresses is by getting to know and organizing with people in our communities. This could be by creating neighborhood support networks, community gardens, child care cooperatives, or unions. Or dinner parties with speeches, and elaborate rituals involving psychedelics. Possibilities will arise.

Smartphones & fossil fuels, or LSD & dinner parties?

Technological progress at some point became synonymous with progress itself. So it’s common for us in the 21st century to think of ourselves as somehow more advanced than those that came before. However this is just semantic confusion disguised as common sense.

In American society we’ve not been able to create a culture, having been disconnected from each other by a confluence of structural factors. There’s the media, which controls what we know and what we value. Work culture, which is precarious, competitive, and often sucks out of us the very life force which we might otherwise use to create good in the world. Then there is the physical structure of society, of cars and suburban homes that isolate us, and screens that are supposed to replace the need for human connection. We are not expected to create culture, but consume it. And we’ve been increasingly fed a culture of bad movies, endless news cycles, and social media. In the end, it is less culture than propaganda.

A life with more storytelling, rituals, ceremonies, initiations, mythology, dinner parties, philosophy, and nature begins to sound like a really good deal in exchange for my smartphone and Google. After 11 months of quarantine, I want to tell stories with my neighbors, invite my friends to dinner to give speeches about love, and share my thoughts with them. I don’t want to Google my doubts or read another Wikipedia article. I want to ask my family, my friends, or my neighbor what they think.

I’m partial to Diotima’s vision of love: that we’re transformed through collective creation. Art, play, celebrations, secret rituals, and dinner parties. These – along with an equitable society where basic needs are guaranteed in a system of mutually owned production – are the foundations of a good human society.

Since our culture is lacking in ritual, we must create it for ourselves. Whether it’s dinner parties, hiking trips, brewing kykeon, searching for artefacts among ruins or sitting in the square contemplating eternal life with our neighbors who are also philosophers, or have the potential to be.

Let the people be the philosophers, and the millionaires, and the psychonauts. Let us all be philosophers and millionaires. It’s your experience, choose. Like a good trip, this task – of being who you are and pursuing what you want, of determining your own experience, of self and collective transformation – is your own creation, and at once very heavy and very light.

And if the economy plays a huge role in our mental health, the environment plays an unseen one. Like Jung’s collective unconscious, nature is visual, and it’s constantly at the back of our minds.

If these butterflies escape us, if our transformation eludes us, so may eternal life escape humanity. Though Demeter’s grass may still turn green, where will the souls go? What will they eat? And what if the river’s water has turned to poison?